[ad_1]

Direct Air Capture (DAC), is one of a number of (still largely theoretical) methods of collecting and sequestering atmospheric carbon currently being looked at. Despite their varied methods, all of these techniques seek to accomplish the same goal: pull carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and sequester it in a form that will not contribute to the effects of global warming.

Bio-energy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) is the most researched technique to date. As plants grow, they absorb carbon from the atmosphere. However, when that biomass is burned in power plants to generate electricity, that carbon is released back out into the atmosphere (a net zero effect). BECCS attempts to capture that carbon as the biomass is burned, then pump it deep underground where the greenhouse gasses will become locked in geological formations. BECCS is already being utilized at the industrial scale, three test facilities located throughout Europe and the UK have been pulling in an estimated 550,000 tons of CO2 annually since 2012.

The other technological frontrunner in the greenhouse gas sequestration race is DAC. Unlike current flue gas capture systems, which can only effectively collect CO2 directly from a factory smokestack where the carbon dioxide is more concentrated, DACs can capture carbon at more diverse and distributed sources. And given that roughly half of annual CO2 emissions come from distributed sources (such as vehicle tailpipes), DACs could have a huge impact on climate change.

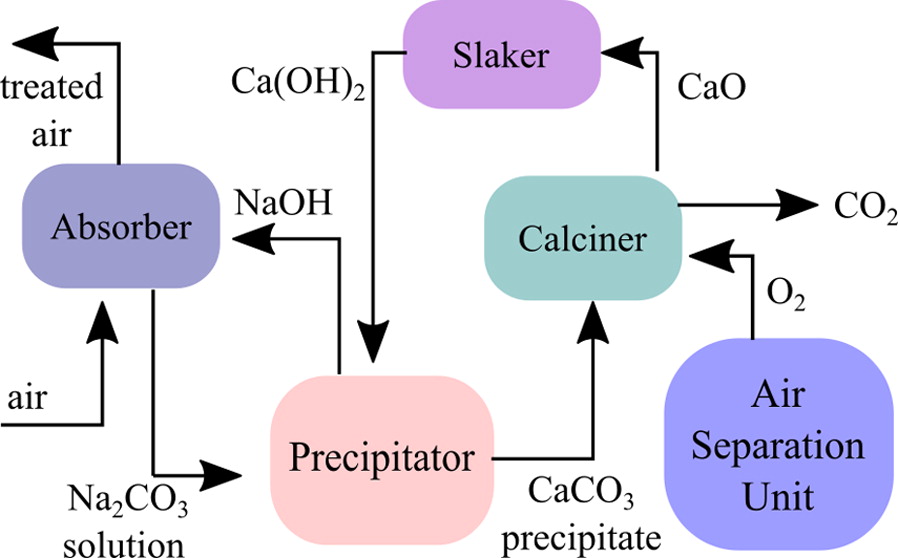

DACs generally operate by pushing air past a sorbent chemical which binds with carbon dioxide but allows other molecules to pass unimpeded. For example, one of the earliest sorbents employed was a calcium hydroxide solution, which strongly binds with CO2 to create calcium carbonate. The captured CO2 is then unbound from the sorbent, purified and concentrated for use in industrial applications. Of course this is often easier said than done. With the calcium carbonate method (which is derived from the Kraft process), the material must be separated from the solution, dried, and then carbonized at 700 degrees C.

This however reveals the Achilles heel of DACs: their cost. A 2015 study from the National Academies estimated costs of around $400 to $1,000 per ton of CO2 extracted at that time. With nations needed to collectively pull 5 billion tons of carbon out of the atmosphere, every year until 2050, to remain within the bounds of the Paris Climate Accord, doing so with just DACs would prove economically infeasible. The associated energy costs needed to carry out these chemical processes (estimated at 12 gigajoules of electricity per ton of CO2 captured) would be equally staggering.

“Direct air capture could become a major industry if the technology matures and prices drop dramatically,” Professor Chris Field, former co-chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC), and Dr Katharine Mach, director of the Stanford Environment Facility, wrote in a 2017 Science article. “Direct air capture might require much less land but entail much higher costs and consumption of a large fraction of global energy production.”

Of course, that’s not stopping a number of entrepreneurs from trying. In fact, efforts over the past few years have already seen DAC sequestration costs drop to between $94 and $232 per ton, according to the journal Joule.

Among the frontrunners is Swiss-based Climeworks. The company, a spin-off from the ETH Zurich university, recently began operating a small DAC system in the mountain town of Hinwil, Switzerland. As ideal setups go, Climeworks has it pretty good. The DAC is situated atop the town’s incinerator, which provides heat to drive the molecular separation process and power to drive the device’s massive fans. A nearby fruit and vegetable company pays around $225/ton of the purified CO2 for its greenhouses.

“With this plant, we can show costs of roughly $600 per tonne [of CO2], which is, of course, if we compare it to a market price, very high.” Climeworks co-founder Christoph Gebald told Carbon Brief in 2017. “But, if we compare it to studies which have been done previously, projecting the costs of direct air capture, it’s a sensation.”

“We are very confident that, once we build version two, three and four of this plant, we can bring down costs,” he continued. “We see a factor [of] three cost reduction in the next 3-5 years, so a final cost of $200 per tonne. The long-term target price for what we do is clearly $100 per tonne of CO2.”

While Climeworks is focused on concentrating CO2 for resale, another startup is taking the opposite approach. The Healthy Climate Alliance unveiled a prototype DAC at the Global Climate Action Summit on Tuesday. And unlike the heat-based system employed by Climeworks, HCA’s system utilizes a resin-based sorbent that collects CO2 when exposed to air but releases it when submerged under water, Peter Fiekowsky, Co-Founder and President of HCA, told Engadget. The seven-foot tall prototype, Fiekowsky explained, should manage to pull between 2 and 10 pounds of CO2 per day and expects that, once the system is scaled up to the industrial level, should operate at a rate of about $30 per ton of captured CO2.

Rather than purifying the carbon dioxide that the DAC collects, HCA sells the CO2 to Blue Planet Ltd, a construction company that sells recaptured carbon-based building products, for use in materials like concrete. The companies hope that this technology will help to open a market for up to 20 billion tons of carbon dioxide per year and a reliable means of permanently sequestering the greenhouse gas in tomorrow’s homes and offices.

Source link

Tech News code

Tech News code